I just came from watching “The Last Full Measure” about a horrific battle called Operation Abilene that took place while I was in country. If you watch the trailer, you will hear a line from the movie that really took me down. I am glad the noon day matinee only had 6 patrons. The Senator portrayed in the film said:

“Usually we are judged by what we do. But what we don’t do is what haunts us.”

I’m alone now in my studio, it’s raining as I stare out my 2nd story window, and I feel like purging something . . . seeing if I can put a particular long time angst to words.

Let me digress for a moment to shed a bit of light on my year in Southeast Asia. I was with the 74 Aviation Company, part of the 145th Aviation Battalion, III Corps, MACV. In 1965 and 1966, an Army pilot who was in it during the day, but fairly comfortable in our company villa, or hooch row, or tent city, or for 2 months, in an appropriated pagoda at Duc Hoa (radio call sign “Ghost Dance” where Capt. Tompkins made the FNG (that would be me) sleep on a top bunk while wearing a flack vest. Point is, I was a kid on an adventure and didn’t have it all that though.

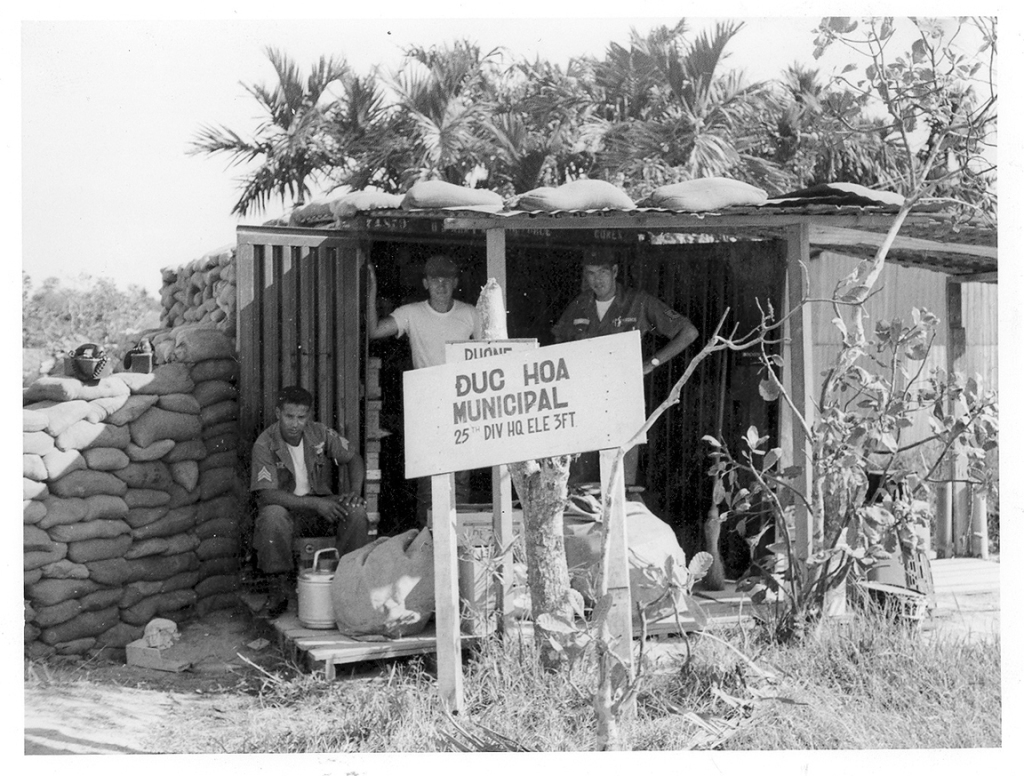

3 Corps included the capitol city of Siagon, and the hamlet of Duc Hoa where, interestingly enough, the 145th (Old Warriors) was the first in combat in Vietnam, and the first air assault mission was flown near here (December 1961) inserting South Vietnamese troops. One H-21 was lost in the action, also a first. Here is the aforementioned Captain Tompkins mugging for my camera at Duc Hoa International Airport, c.1965.

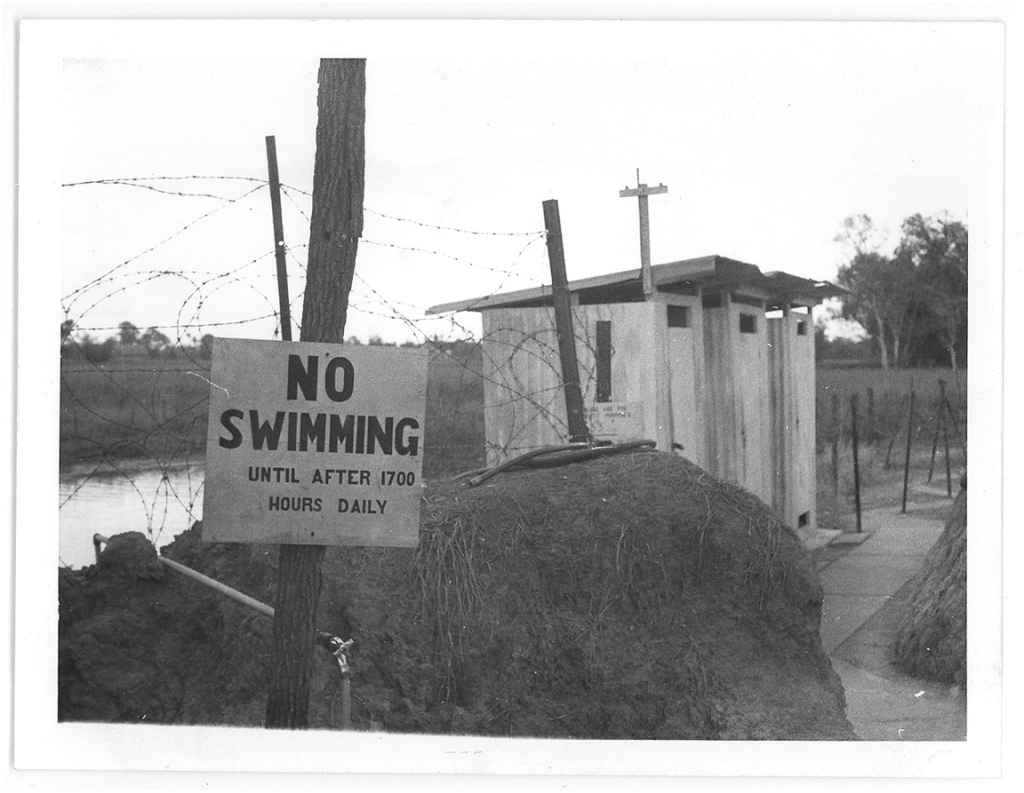

Crew Chief’s shack (left) at the Duc Hoa air strip, Vietnam c. 1965. The unit comfort stations are pictured above right, and they dumped into Duc Hoa pond. Swimming was forbidden for obvious reasons. However, locals waded chest deep in Shit Lake to purse seine for huge carp.

So here I was in a historic village where the US involvement in the war began 5 years earlier, soon to turn 21 in a strange place where life got real fairly quickly on a daily basis. Even so, I was a unicorn of sorts as I was a fixed wing (airplane) pilot rather than the more common fling wing (helicopter) pilot the army was rapidly becoming know for. The 74th Aviation Company operated a couple of dozen Bird Dogs, 2 de Havilland Beavers and a twin Beach L-23 Seminole.

As you might guess, most of my flight time was just as the patch suggested, observation and reporting. Other common missions were convoy escort to include trains before the tracks were blown up, artillery adjustment, and forward air control for our Army gunships, as well as Air Force, Marine, Navy and ARVN fighter/bombers when their own FAC planes were not available. We were also used as bait in the early years, tasked with flying low over roads and highways in the relatively flat 3rd Corps terrain looking to pick up small arms fire. We relied on the fact that by the time Viet Cong heard us, there was precious little reaction time for them to get off an accurate shot. I would steep turn one way or the other, toss out a smoke grenade to mark the offense, and call in gun ships. Pretty soon, the VC learned to put hai and hai together and not to shoot as us because of what we could bring to bear.

We also flew radio relay when search and destroy ops were too far away from base camps, especially at night. No satellite comms in 1966. We were the unit’s lifeline should anything happen while out on patrol. One mission was to fly in a large orbit over the Mekong River petroleum tank farm in 5 hour shifts at night in case they got mortared. No autopilot back then, but I would trim the airplane up and doze a half hour at a time knowing that the radio checks on the hour and half hour would wake me. So you see, our missions weren’t very glamorous or fraught with eminent danger, however we had our moments. The best thing I could ever do was call in an air ambulance Huey, or Dustoff to medivac wounded, often very soon after it happened. This part of our mission was more gratifying to me that anything else, be it calling in Huey gunships, Air Force F-4 Phantom jets, Puff the Magic Dragon . . . . ANY other radio relay task!

I regret that I was never at an airbase where Dustoff crews were billeted, and so only “knew” them by radio conversation in the heat of battle. These guys were my heroes. “That Others May Live” was embroidered on many of their unit patches. They had titanium balls before titanium was even popular! In April of 1962, the 57th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) arrived in Vietnam with five UH-1 “Huey” helicopters. They took the call sign Dustoff. Over time the number of medivac detachments grew in Vietnam until the entire country had coverage and Dustoff became the universal call sign for all medivac missions.

A Dustoff crew consisted of two pilots, a medic and a crew chief. Usually, one pilot would fly the helicopter while the other acted as the aircraft commander. The commander would navigate, monitor all of the radio transmissions, talk to the unit requesting the medivac and would take over flying if the pilot were injured. The medic kept the helicopter stocked with the necessary medical supplies and the crew chief would maintain the helicopter in top working condition. They would both load the patients onto the helicopter and the medic would administer any necessary medical treatment on the way to the hospital, often with the help of the crew chief. Except for the Medivac helicopters of the 1st Air Cavalry Division, these air ambulances carried no armament heavier than the pilots’ M16 rifles, and most of the Dustoff missions were executed by a single ship rather than a well prepared team to include gun ships. Yeah, these guys flew well prepared, but absent fear or trepidation. They were my aviation idols. So one would think, given the opportunity, that I would jump at the chance to be like these pilots I so admired . . . . one would think. But as Paul Harvey would say, here is the rest of the story.

I came home from Vietnam, went to MOI (Methods of Instruction) school back at Mother Rucker, got married and settled into the “Big Man on Campus” flight instructor roll at Ft Stewart Georgia just outside historic Savannah. Life was good! The war raged on. As I was closing out my 4 year obligation to the Army in 1968, and busied myself with teaching the very hero helicopter pilots I respected so much to fly airplanes and thereby become dual rated, I got a note to see the CO. Captain Noyes offered me a choice, one that I so flippantly made on the spot. He said I could go back home to San Diego on the Army’s dime, since that is where I enlisted years ago, or that there was plenty of space in Helicopter transition school at Ft Rucker if I signed for another 4 years, and then back to Vietnam in the outfit of my liking. My wife was expecting our first son. I politely and with no hesitation, turned my back on my heroes and asked how much travel money I would get to travel from coast to coast. I sent others to fight in my stead.

I didn’t think twice about it until 15 or 20 years ago, when I enrolled in VA Health Care to be screened for Agent Orange symptoms, PTSD, hearing loss and sleepless nights. I slowly but surely started to sleep the sleep of a haunted man. I don’t believe the VA has a cure for my conscience. I had a chance to be that guy I respected, honored and admired for his courage under fire, to aquire his skill set and earn his reputation.

“Usually we are judged by what we do. But what we don’t do is what haunts us.”

I have talked this over with family and friends alike, and it helps for a while. They do their best because they care about me. I buried this for so long as I tried to grow a family and a business. But like an Edgar Allan Poe wall clock, time catches up to me in the middle of the night.

“’Is there – is there balm in Gilead? – tell me – tell me, I implore!’

Quoth the Raven, ‘Nevermore.’”